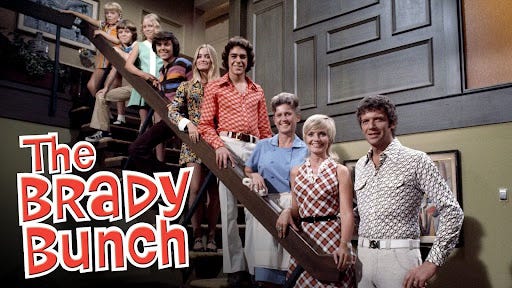

The Brady Bunch, and by extension its creator Sherwood Schwartz, ruined my life.

It’s embarrassing, but I don’t remember exactly when I realized I had unconsciously used the Brady Bunch as the bar by which to measure my life. There’s a distant bell that rang sometime in my 30s – a moment when I thought, hey, there’s nothing wrong here; this mess you are standing in, it’s just your life, and no, it is nothing like you were led to believe as a child.

“It’s one world, and we all have to live together,” Sherwood Schwartz

Sherwood didn’t set out to harm an entire generation; he wanted to offer a model of community that we could learn from and emulate (Gilligan’s Island, was also his). I learned a lot, but what I learned was a lie.

Our TV was downstairs in the family room. My parents watched their programs, and I often did too, Walter Cronkite every evening after dinner, and then maybe McCloud or Columbo — white men solving crimes; white men in charge — but my parents didn’t watch my programs. Kid TV was for the kids.

When the television beamed its magic across the olive-green shag carpet to find me glassy-eyed on the couch, I was all alone — just me and my shows; helpless, in that way children are, ill-equipped to judge or think critically about things. Children believe, which is both the magic and the danger of childhood. We are a tiny tabula rasa waiting for any person, the good, the bad, to write themselves all over us. I was wet clay in the hands of Sherwood Schwartz and his dangerous utopian visions of human relationships.

My tenuous self-worth was pegged to the standards prescribed by the Queen, her Royal Smugness, the skinny, popular, and blonde Marsha Brady. I had brown curly hair = fail; I wasn’t stick thin = fail, and I wasn’t popular = a perfect trifecta of failure.

Moreover, my parents didn’t have all the answers the way Mike and Carol did, had I ever even thought to ask them, which I didn’t. To my folks, kids were self-rising like bread: put us in a warm place and do not disturb until fully grown. This hands-off approach to parenting might be another reason The Brady Bunch had such an outsized influence on me: my New England family was nothing like that hip, sunny house of wise parents who cared about your grades, friends, and what you were up to after school. Childhood was a gauntlet. For me and the rest of my 1960s cohort, it’s a miracle any of us made it out alive.

And yet, despite knowing better, I still harbor a deep nostalgia for the comfort food of my childhood TV programs, however, when I went back to watch a few episodes, I could hardly choke down one.

Season 1, episode 9: the kids are using the phone too much (remember landlines?). Mr. Brady (Mike to his friends) installs a payphone to solve the problem, but uh-oh! Now the kids are fighting over dimes and nickels to use the phone. This was 1970s drama. Admittedly, these days I pine for simpler times; however, I’m less down with imbecilic ones. Sherwood meant well, but he showed us life, impossibly perfect, to the point of anemic.

What was happening? The show I once loved had lost all of its charms. Yes, it’s a fabulous time capsule: bills are paper, and you write checks to pay them, and the 1970s fashion and hair was chef’s kiss. But otherwise, it left me uneasy and bored.

Beyond the vapid plot lines, what struck me was how empty the characters were — as a kid, I saw Greg Brady as a fully formed person, a guy in charge of whatever 13-year-olds are in charge of — the Brady clan was a pod of perfect beings closer to aliens or androids than humans. Mrs. Brady (Carol to her husband) was giving full-on uncanny valley with her almost, yet not entirely, human reactions. And the weirdly rigid kids, more like mini-adults than actual children. The sterile kitchen in which no one, not even Alice, cooks. This is not a home; it’s an institution. Why had I ever wanted in?

So true. Can’t believe this and Gilligan’s Island, I Dream of Jeanie and Bewitched held us enthralled. So shallow and the gender and general politics oh my god. Have you seen the brilliant PEN15 as a contemporary antidote?